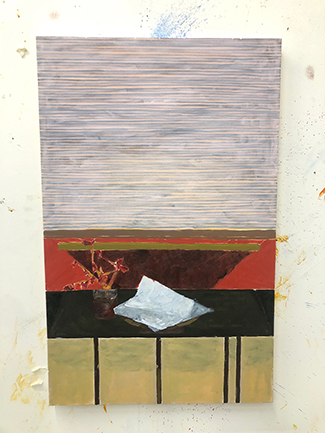

Fine Art

When art students finish their education and meet the world, the conversation might go something like this:

– What do you do?

– I’m an artist.

– Oh… but what do you do?

A simple exchange — but one that says a lot. About how we measure work, how we understand knowledge and what we believe art to be. It’s as if art doesn’t quite count as work unless it can be explained, sold, or connected to something useful. At the same time, that repeated question — even when it has been answered — shows us that art operates where logic, language and existence blur and fall apart, where the question is a window, and the answer a mirror.

It is often in this very fracture — where logic fails, and emotion resonates — that young artists begin their work today. After a period where many artists have used photography, performative or documentary methods to expose hidden power and give form to the disregarded or unheard, we meet art as an increasingly existential practice in Konstfack’s Degree Exhibition 2025. Whether political, abstract, intuitive or conceptual, the work is less about saying something and more about the act of expression itself, like a voice finding itself by sounding out. By breaking with aesthetics and disrupting the expected within established forms, expressions and media, the artwork becomes a kind of critique — not of representation or content, but of the very conditions of perception.

Asking an artist what they do is a fair question if one assume that artistic work and its value can be defined in many ways. And we do. At the Bachelor’s programme in Fine Art, teaching is based on the idea that each student carves out their own artistic path. Technique and theory are taught in ways that deepen and support each individual’s work.

But making art also trains another kind of knowledge. Knowledge that applies not just to the artist, but to all who take part in the artistic educational space: students, teachers, administrators and visitors. It’s the ability to listen, to hold space for uncertainty and make room for what seems impossible. On an ordinary day at work, this might go something like this:

– What do you do?

– I’m trying to understand something I don’t know what it is, using tools I haven’t quite figured out yet and a language that might not exist.

Loulou Cherinet

Professor of Fine Art