Fine Art

The materialities of art can be described as a sort of artistic journey through what might comprise a material for an artist to work with or through. Everything from traditional materials such as clay, wood, paint, canvas, and so on, via modernism’s embrace of readymades and industrial materials, and on to conceptual art’s dissolution of the object.

It can be an interdisciplinary approach that in art history research also comprises studies of the significance and agency of the material in relation to humans, society and culture.

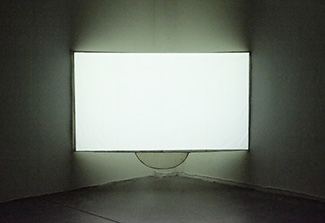

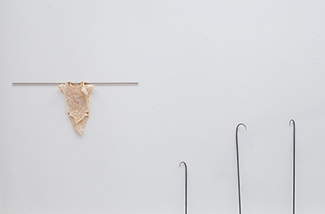

Above are two examples of how art in all its forms can be contemplated, researched and exhibited. The examples concern trying to understand, identify and define the often-elusive concept of materiality. Or perhaps the even more elusive – the materiality of art.

The students graduating from the Master’s programme in Fine Art this year are all (!) in various ways engaged in working with different materials, most of these physical materials (or works that in some way relate to a physical, existing material). We recognise painting, sculpture, photography, film, readymades in different forms and executions, which are all to varying degrees processed, compiled, arranged and presented. In relation to the presentations are site-built walls and shelves, projection screens, podiums, suspension devices, projectors, speakers, media players and lighting. The degree projects are presented with their front and back sides equally visible. We see remnants of how works came into being in the form of joints, grinding, putty, dried paint, glue residue. We can also study maps of the installations, lists of titles, descriptions of works, various kinds of texts related to the exhibited works. In addition to the displayed ‘works’ themselves, there is an abundance of materials that are of lesser or greater importance to the understanding and experience of what is being exhibited, and often also a part of the work.

But is it precisely the working and arrangement of materials that creates materiality? On superficial consideration, it is easy to answer yes to this question (a material yields, when processed, a materiality), but perhaps the concept needs to be understood as something greater than this? So many other things affect how we understand an artwork and, with it, its materiality. We are speaking of context and connection, and we are speaking of history and relationships.

The German artist Martin Kippenberger asserted in an interview that pasta was an important component in the understanding of contemporary painting. A far-fetched example of course, but with this he wanted to call our attention to the fact that there are infinitely more things that affect how we experience an artwork than only that which we have in front of our eyes at that moment. All the information that is incorporated into and that exists in relationship to a presented work is what collectively creates the work and fills it with content.

This is how the agency of the material in relationship to humans, society and culture comes into play as a factor in how we can understand the concept of materiality. Perhaps it is something that we can most easily understand as a statement from each artist about their own relationship to, and interpretation of, what an artistic material is and can be, how it is filled with different sorts of content, and how it meets the world at a given moment.

Thomas Elovsson

Professor of Fine Art